|

In Memorium: HIV/AIDS Pioneer, Medical Researcher, Songwriter and Entrepreneur Allen D. Allen |

Allen D. Allen was a creator. Throughout the evolution of his life, Allen's natural curiosity drove him to create simple solutions to complex problems. Always ahead of his time, he was creating apps before computers had screens and keypads. His early theories of depression and disease are resonating today. Most significantly, his efforts in HIV/AIDS have led the industry and saved lives. After a long and principled life, Allen D. Allen passed away on March 23, 2017.

Allen found success as a songwriter and as a medical researcher. The skill set is the same. A Medical Researcher can be found at most university teaching hospitals. Their job is to observe and ponder. In the academic world of "publish or perish," a medical researcher is looking for an interesting topic to investigate and launch into a study. It is a job that requires equal parts hope and skepticism. So is songwriting. The freedom of a melody must be constrained by time and measure.

Allen found success as a songwriter and as a medical researcher. The skill set is the same. A Medical Researcher can be found at most university teaching hospitals. Their job is to observe and ponder. In the academic world of "publish or perish," a medical researcher is looking for an interesting topic to investigate and launch into a study. It is a job that requires equal parts hope and skepticism. So is songwriting. The freedom of a melody must be constrained by time and measure.

Educated at Berkeley and UCLA, Allen D. Allen eventually landed into his desired role as a medical researcher in the 1980s. "I am very curious," says Allen, "I like to pour over random case files, because, at some time, a pattern develops and there is that "Eureka" moment of a discovery."

Prior to this, Allen found success in two very different, yet related, fields. As a songwriter, he composed a few hits, namely "Just Married", a famous hit record by Marty Robbins. Advertising jingles proved to be the most lucrative. In the Sixties, Allen worked with many ad agencies and confesses, "It really was just like Mad Men." He wrote and produced jingles for many products, such as Toyota, Sun-Maid Raisins, Manischewitz Wine and Schilling Spices.

Later in the decade, Allen founded a computer software company, long before computers had screens and graphics, back when a paper key card was strategically punched with holes to create calculations. At the time, IBM was focused on accounting solutions and Allen began to create new business applications for scheduling and efficiency. Later, he sold the company and made his move into medical research.

Music and computers are very similar in their construction and application. Hard and fast rules are observed and innovated. Medical discovery is produced in the same way.

Much like a detective, he studied hospital medical charts looking for similarities and anomalies. The role demands objectivity, but Allen had his biases.

Allen had a compelling need to study and fight depression. "It became my calling." As his mother entered menopause, she grew progressively depressed. Years under a psychiatrist's care produced no results and nearly bankrupted his father. His mother suffered and no relief was available.

Creating confusion for doctors, an overreaction of the immune system will cause depression and anxiety, both symptoms of other diseases. This fueled Allen's inquisition of the relationship between the mind and the immune system, an interplay of which much is yet to be discovered.

"Women are most susceptible to certain physical diseases that produce mental symptoms, such as depression and anxiety," said Allen, "For decades they would be sent to psychiatrists who couldn't help them, instead of seeing rheumatologists, the doctors who could provide appropriate and effective treatment."

This fact was evident during the Epstein-Barr crisis. In the 80's, men and women were misdiagnosed as having the Epstein-Barr virus, when in truth, they were suffering from depression. The incorrect reading of a blood test was misleading doctors across the nation.

Allen studied the flood of Epstein-Barr cases and discovered the mass misdiagnosis. This research alerted him to the importance and potential possibilities of blood work.

In a recent paper in the International Journal of Clinical Medicine, Allen explained how the elevated antibodies for certain viruses can detect depression and bi-polar disorder. "Such a test could prevent horrific tragedies, such as the suicidal crash of Germanwings Flight 9525 on March 24, 2015," he said.

In the early 80's, a mysterious, new disease overwhelmed Allen's studies as well as the rest of the medical community and the world. The AIDS virus was a vicious, unknown killer.

At Olive View-UCLA Medical Center, Allen had access to a great deal of data and university findings. He began to see mathematical patterns in the forces of the AIDS virus.

Allen was most curious when it was discovered that the AIDS virus infected chimps, but did not make them sick. Why was AIDS killing humans? How was the human immune system

different?

In the same way that a composer creates a song or a software engineer designs an application, Allen wondered if one could modify the human immune system to solve this problem. He began to realize that a monoclonal antibody (MAB) could change the immune system so that it would stop "helping" the AIDS virus.

The future of medicine is full of hope, theory and opinion. AIDS was, and is, a frightening epidemic and the hysteric reaction of social and political forces were creating great pressure on the medical community that was grasping at straws to find a solution. New theories and treatments were proposed, tested and often failed. New drugs were creating dangerous side effects and even killing patients. Often doctors think in a herd-like mentality. At the time, most experts believed that a MAB antibody could never be used as a treatment.

Fred Chris was a gay man with AIDS and a friend of Allen Allen. He became the first to receive a monoclonal antibody. The results were instantaneous. Symptoms, such as skin lesions, vanished overnight and his T-cell count climbed. The damage, born of the AIDS virus, was halted.

A second, third and fourth patient were treated. The results were miraculously the same. On the West coast, word began to spread among the desperate AIDS doctors. The doctors treated two to three hundred patients with the antibody. Data from 188 patients were eventually submitted to the FDA. Unlike most other AIDS treatments, there were no serious side effects and no one was dying from it.

The elation that Allen felt was soon deflated. Armed with his data, he approached pharmaceutical companies and venture capitalists to launch a study. The expert medical opinion believed that a monoclonal antibody could not be used as treatment. Allen was kicked to the curb.

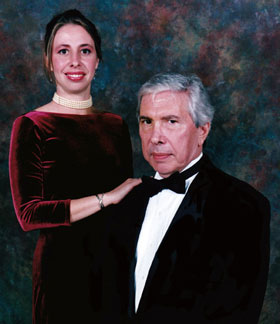

The patients who had been successfully treated and their friends and family conferred with Allen. They created and funded a privately held company, designed to launch a formal clinical trial. With approximately thirty-five shareholders and his eldest daughter Corinne, who had become a CPA, CytoDyn, Inc. was born.

There is really only one way to introduce a new medical practice or a drug. The proper and established method is a clinical trial approved and supervised by the US Food and Drug Administration. The process is time consuming and expensive. CytoDyn needed capital.

Allen gave his patents, the reins of his innovation, to a dynamic and persuasive entrepreneurial group that was to raise funds and conduct the trials with a publicly traded company. His work done, Allen waited for the results, the fruit of his labors.

The stock of the publicly traded company was a success and began to sell millions of shares in a day. But the clinical trial was never started. The leader of the entrepreneurial group turned out to be a con artist. To protect his discovery and his colleagues, Allen had to get legal.

Three years after receiving the first injection, Fred Chris died. He succumbed to another disease often found in AIDS patients, Hepatitis C. At the funeral, Allen was feted as a hero for extending Chris's life. "But I felt like a failure," he says, "Because I did not save my friend."

Back in the game again, Allen spent the next two years waiting in court, trying to recover his patents, which were finally returned to his control. With new management, CytoDyn was ready for business as a publicly traded company. Over 10 million dollars was raised in new capital. With the acquisition of Pro 140, a more developed antibody, CytoDyn began a Phase IIB clinical trial. The company reported spectacular results.

Corinne and her father Allen D. Allen |

With his discovery secure, Allen Allen officially retired in 2011. "Like anybody in their Seventies and Eighties, I now spend most of my retirement going to some doctor or another," laughed Allen. He and his wife Annette had recently celebrated their fifty-second wedding anniversary.

"I think the hardest part of the journey has been the realities of the medical industry," said Allen, "Big Pharma is risk-averse. They are not interested in innovation, but in selling pills. That was the hardest reality."

After a long and eventful life, Allen D. Allen has passed away. His eldest daughter Corinne now carries on his legacy. "Working along side my father for over 20 years, I watched as he could solve any problem, make hard decisions and keep his integrity intact," said Corinne, "He remained loyal to his science, his family, his friends and his shareholders. Whether it is music, science or medicine, my father's life works will continue to have profound effects on the world for years, maybe even centuries. It is a great loss for me, our family and our civilization." He is survived by his wife Annette, his daughters Corinne and Jacquelyn, his son Gregory and his granddaughter Elsa.